When the past returns to the present

“The past is never dead. It is not even past.” William Faulkner

Some stories, no matter how much times passes, just never disappear. Over the past couple of weeks, a series of stories highlighted such history to the Houston sports fan. First, the former Houston NFL team (Tennessee Titans) announced plans to abandon their throwback uniforms, the Columbia Blue jerseys with the oil derrick helmet logos. Probably for the best, as they were only 1-2 in those, and both losses came to the Texans at home. Yet, they will incorporate their historic Columbia Blue color (now “Titans Blue”) into the new design, for their home jerseys.

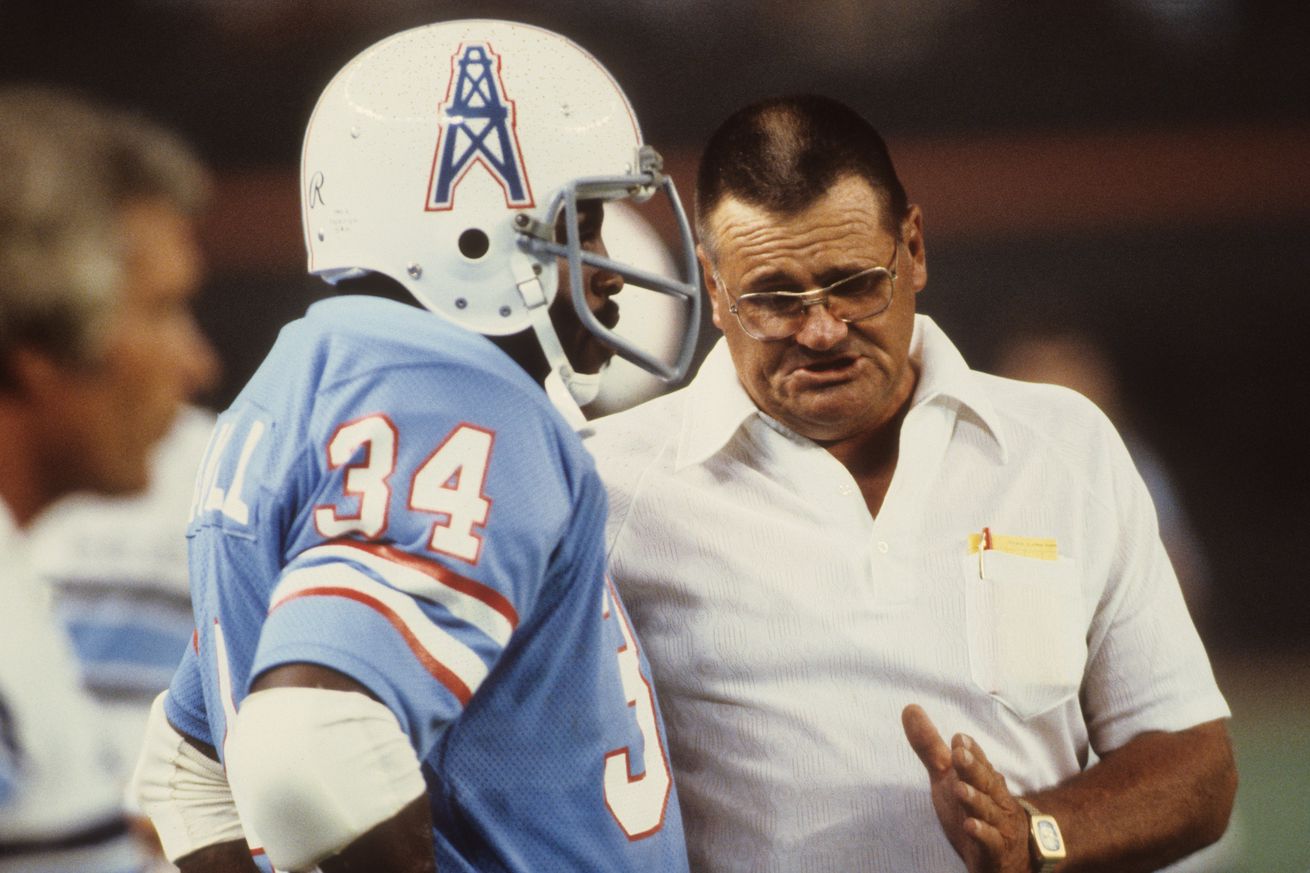

Then, in Houston, a documentary about Bum Phillips premiered (Luv Ya, Bum), which brought to mind perhaps the golden age of the Oilers in Houston. In the late 1970s, the Luv Ya Blue days dominated Houston, when Bum Phillips prowled the sidelines with his ten-gallon hat and ostrich-skinned boots, Earl Campbell bulled through defenses and the Astrodome was awash in blue pom-poms and signing “We’re the Houston Oilers…” ad nauseam. A fun time in the past, but one that highlights the struggle for the history of pro football in the city of Houston.

Then the Athletic got in on the act, recounting the Titans’ jersey decisions and the long back-story of why a jersey color is a point of contention between Houston and Nashville. For events and deals made over 30 years ago, with many of the principle players long retired or deceased, it is interesting that people still hold ill-will related to a color on a uniform. Jerry Seinfeld once observed about sports fandom that people will cheer for laundry. The point was that making such a big deal about a name stitched on a piece of colored cloth for an athlete hardly qualified as a big deal. Yet, here we are.

Roughly 20% of Houston’s population was not alive the last time that the Oilers played in Houston and a generation of people know only the Texans as Houston’s pro football team. Yet, there remains a significant portion of the population that remembers when the Oilers roams the Astrodome, when fall Sundays in Houston centered on the Oilers, playing games in the “House of Pain.” Along with Campbell and Bum, you had personalities from Dan Pastorini, Elvin Bethea, Warren Moon, Ray Childress, Mike Munchak, Bruce Matthews, Ernest Givins, Sean Jones, Jack Pardee, Jerry Glanville, even something called a Giff Nielsen…donning the Columbia Blue.

Of course, while the “House of Pain” moniker mainly sought to convey the tough day that opposing offenses could expect in the Astrodome, it also could sum up the fandom of being an Oilers fan. Those Luv Ya Blue days took Houston fans on some great rides, but they all came to a crashing halt against the peak of the Steel Curtain Dynasty of the 1970s. Back-to-Back AFC Championship losses to Pittsburgh in the 1978-1979 season would be the closest that a Houston based team would get to the Super Bowl. The Oilers of the late 1980s-early 1990s offered up some of the most talented teams in the league, consistently among the league-leaders in Pro Bowlers (back when that meant something). However, their player talent was only matched by the creative ways they failed in the playoffs. Seven straight playoff appearances. Not even a single conference title game appearance. The last three of those playoff trips: The Drive Part II , The Comeback in Buffalo and the 4th quarter collapse against Kansas City in the last playoff game in the Astrodome.

The Athletic recounted the political maneuvering undertaken by Adams and some lawyers to try to convince the city of Houston to work with him to get a new stadium done. However, Adams’ previous threats to move the team (primarily in 1987 when he nearly moved the squad to Jacksonville) proved politically costly. By 1995, when Adams made new noises about a new stadium, he hadn’t burned his bridges, he nuked them. The subsequent radioactivity made it such that no political figure in Houston would support him. Not discussed, but a significant factor, centered on the constant near-misses from the Oilers. Throw in the disastrous teardown/collapse of the squad in the 1994 season, and the fans were done. A motivated fanbase might have swayed Houston to consider making a deal with Adams, but the overwhelming apathy of the Oilers fans offered Bud Adams no support. Thus, when the Oilers agreed to move to Nashville, the response: don’t let the door hit you in the [KITTEN] on the way out.

Houston Chronicle via Getty Images

Yet, when Houston booted him out the door, Houston, so wanting to be rid of K.S. Adams, allowed Adams to keep the team’s history and colors. At the time, it didn’t seem like that big a deal. Houston didn’t know if or when it might return to the NFL, and the colors, once so venerated, just didn’t resonate with the city any more. Even with Bob McNair brought the NFL back to Houston (at a far costlier price than if the city had dealt with Adams in the mid-1990s), there was no discussion about bringing back the Columbia Blue. Likely Adams would not have consented to return the color to Houston even if McNair asked. While many in Houston revile Bud Adams to this day, Adams never got over being persona non grata to his home city and his pride in the team and all it stood for ensured he would never give that up.

Fast forward to the 2020s, and now that debate returns. Personas such as JJ Watt have called for the return of the old Oilers colors to Houston. Yet, the stubbornness of the Adams family to hold on to that legacy is just as entrenched as ever. Primarily, the current owner of the Titans, Amy Adams Strunk (daughter of Bud) holds to that tradition as stubbornly as her father (who passed in 2013). Likely she’ll never surrender that prerogative, and there is little to suggest that the NFL will step in to change that.

At this point, with the big free agency moves mostly done and the draft still a month away, stories like this at least fill the dead space in the NFL calendar. Given that a vast majority of the players on both rosters weren’t even alive when the Oilers last played in Houston, this story is nothing more than background noise. As time moves forward, the memories of the Oilers will fade and fans will return to the on-field concerns. Yet, for many of us who grew up with the Oilers, this still brings up some old memories, good and bad. Ideally, we don’t have these discussions of colors/etc. Likely a compromise could be in the offering, but sometimes, the potential of the present can’t get beyond what transpired in the past.