What if the commissioner of baseball answered to more than just the owners?

As we continue down the long road of the baseball off-season, a few things become apparent. One is that people tend to enjoy the coverage/speculation about off-season moves as much as they do whatever happens on the field. Another is that we see too much of Scott Boras. Yet another is that we have to deal with Rob Manfred, or whoever wears the mantle of the commissioner of baseball.

As it stands right now, the “Commissioner” of baseball is the figurehead who speaks for the game. Yet, the reality is that the commissioner is but a focal point/spokesman (so far, all men) for the owners. Currently, baseball selects its commissioners to five year terms, with the collective of owners holding the power to hire and fire said commissioner. As a result, the commissioner tends to speak mostly for his primary constituents. He deals with the players, but more often than not, that relationship is adversarial. As for the fans…yeah, well, anyway.

However, what if the commissioner was not selected by just the owners? What if the commissioner of baseball was selected by both the owners and players?

On one hand, what difference would it make if the commissioner answered to both owners and players? Said individual is still just a corporate suit. What sort of slash line does a commissioner come with? Any applicable WAR stats associated with this individual? No, ok, then we don’t care. The only time we should ever see the commissioner is when he hands over the World Series trophy and perhaps at some sort of state of the game update. The more the commissioner appears, the less anyone wants to deal with him.

And yet, a Commissioner that must answer to not just one set, but two sets, of constituents that can determine the status of the job, that might alter a few things. For one, when the Commissioner comes out to speak about an issue, his remarks and stances need to account for more than 30 individuals/small groups who’s main interest in the game involve their bottom lines. He also must account for the needs and ambitions of perhaps the most visible aspects of the product: the players. Sure, the players have their own agendas and concern for their bottom lines. However, competing agendas can drive a hard degree of compromise.

Consider the labor issues that seem to forever plague baseball. The only things that ever cancelled a World Series since 1903 involved money and labor disputes. The 2020 season nearly died in infancy not so much due to the COVID pandemic and health restrictions, but mainly due to massive disputes over revenue allocation in a shortened season. The 2022 season saw a lockout upend the start of the year. While baseball does have a set collective bargaining agreement, that expires at the end of the 2026 season. Expect there to be plenty of legal and media posturing, with the high likelihood of a lockout or some other form of season disruption.

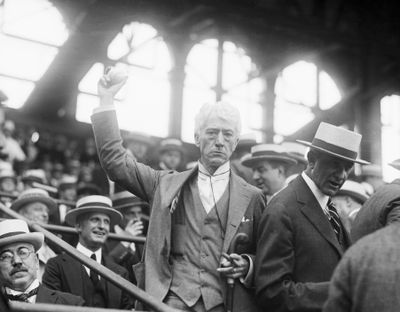

Maybe this calls for a commissioner with near autocratic powers not seen since Judge Kennesaw Mountain Landis ruled baseball from 1922 until his death in 1944. Brought into power by the owners of the American and National League on the heels of the Black Sox Scandal, Landis lead baseball more on his terms vs. the owners. Most noted for his lifetime bans of the “Eight Men Out”, Landis also took on the owners and usually won. While the players got no say in his appointment, he often took their requests/petitions to heart, at the expense of some of the practices of the owners. Landis’ fights against teams that near-monopolized the minor-league systems, owners involved in betting on teams and taking the decision about player suspensions out of the owners’ hands seems unreal for the modern game. Was Landis perfect? No. as evidenced by his upholding baseball’s status quo on its de facto prohibition on allowing African-American players into MLB ranks.

Likely the Landis example forever remains a one-off. The owners tolerate no dissension to their positions, as Fay Vincent found out as the owners all but forced him to resign as commissioner in 1992. While other commissioners after Landis fought the owners, the current trends, especially with Selig and Manfred, see the commissioners generally in lock-step with the owners. Yet, a commissioner does need the ability to keep the owners in line with some power.

As for the players, they historically don’t love the commissioner office. Suspensions and discipline come from that office, so there is already some adversarial relationships baked in, but with the current evolution, the commissioner is even less connected to the players. Misstatements, especially from Manfred, offer him little support from the players (see calling the World Series Trophy a “hunk of metal” and his hemming and hawing about what he did and should have done regarding the Astros). However, without the players, the game doesn’t happen, and a commissioner does need to account for the needs of the players.

Could giving the players a say in the selection of the commissioner change that? The benefit is that the commissioner might have more power to actually lead the game and make those changes that MLB requires for a better overall product. Thus, when labor issues start bubbling up, a commissioner who both the players and the owners can offer a more nuanced stance, one that accounts for the needs of both sides. The ideas of strikes and lockouts, while never completely off the table, might find a less-receptive audience from a commissioner that both factions voted into office.

There is the difficult balance to maintain, as the players’ union and the owners will not broker another Landis. However, if the players and owners had a 50/50 share in the voting in (and removing of) a commissioner, then said individual receives an implied mandate to make the best decisions for the game with the support of two important factions. This might limit, but not remove, the role of the player’s association and the owners, as someone will end up as a focal point for specific issues. However, a commissioner-approved action, be it labor, rules of the game or personnel matter, would have the foundational support of tacit approval, since both players and owners put this person into a position of power to speak for the league.

Will this solve the problems facing the game? Probably not. At any rate, the current system will see Manfred serve as the commissioner of baseball until his term ends in 2029. The priority issues for baseball don’t seem to include revising how to select a commissioner, but if it could tone down the heated and historic rhetoric between ownership and the players, it might reduce the threat that labor issues always seem to plague the American Pastime.

Still, this is just one opinion. What do you think? Would changing how the commissioner comes to power help, hurt, or mean nothing for the game? Let your (respectful) take popular the internet below.