Where does former Astro Joe Morgan stack up?

Sports fans in general are fascinated with excellence. It’s easy to understand why. Guys can sit around the barber shop and sports bar and argue vehemently over who is the best ever. I reiterate the same thing I do in every instance. The index was not designed to rank order players. It also does not definitively say who should be in and who should be out.

It acts as one of many tests we can perform to help answer that question. Any debate over the best ever would have to include the same methodology. As fun as that debate is, we go through this exercise for one other major reason. When we are looking at potential Hall of Famers we have a tendency to compare them with the entire group and that includes the very best of the best. That’s not horribly realistic.

So, what we have done (I did this with catchers and first basemen) is remove the outliers on the upper and lower end. We are not saying anyone is or is not really a Hall of Famer. What we are doing is comparing players with like players. If we compare potential Hall of Famers with others that are statistical fits, but not overwhelmingly so then we have a much better chance of getting it right.

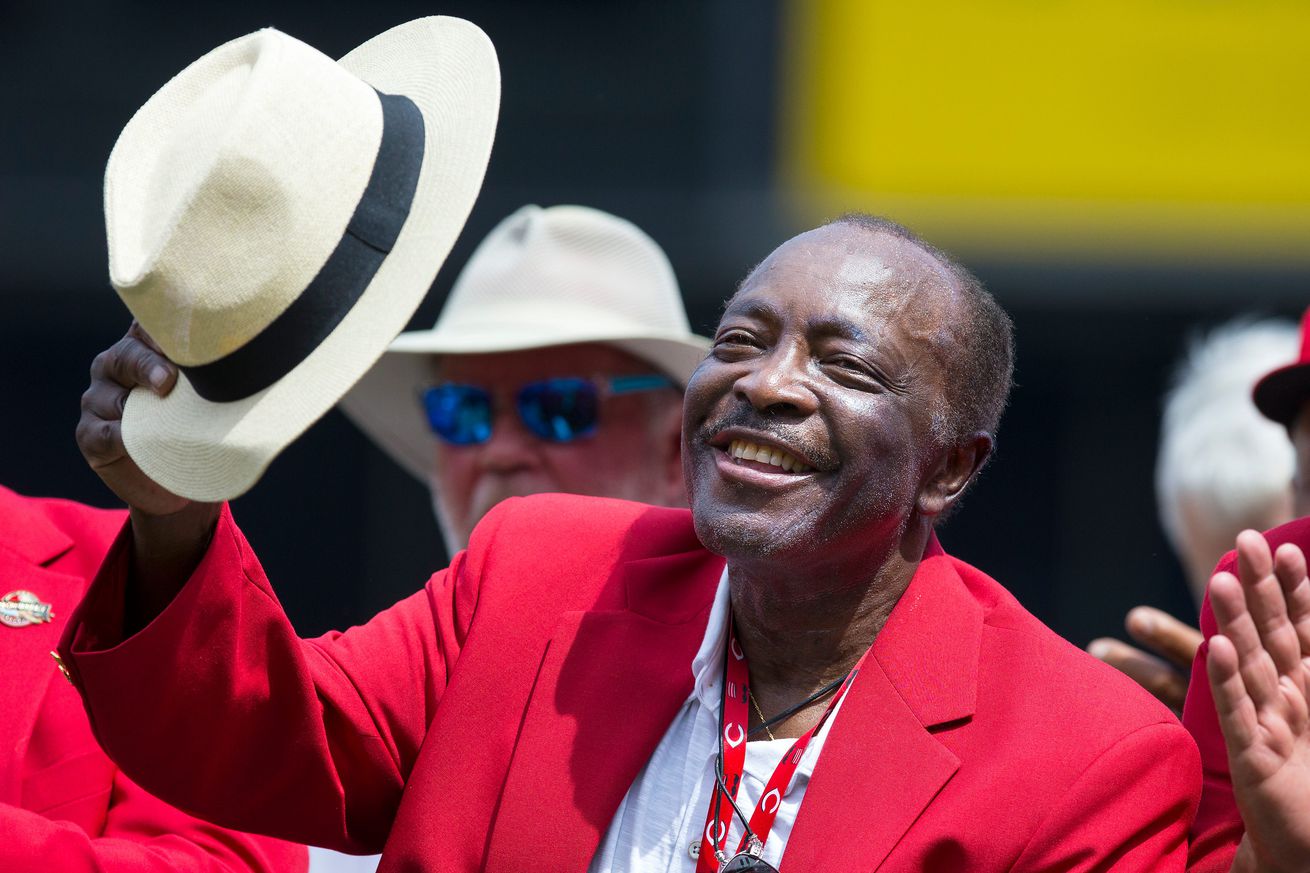

These numbers present something of an SAT question. Which one of these doesn’t belong? Joe Morgan sticks out like a sore thumb; His batting average is way out of whack. Yet this is one of the reasons why we don’t rely on counting numbers. You’d think that he doesn’t belong in this group, but we aren’t including all of the numbers that matter.

As an announcer, Morgan infuriated me. There is nothing more mystifying that someone that doesn’t understand his own greatness. Yes, Morgan had power and speed and that made him valuable. What made him more valuable was his ability to steal first base. Yet, he spent his entire broadcasting career discounting the importance of on base percentage. It was almost to the level of self-hate.

Beyond that, you have the issue of home ballparks and the eras these players played in. Relying on counting numbers alone is foolish, but we can see the folly of comparing candidates with these guys. When we see the index numbers we see that Morgan really does belong and with the other tests we can even begin to see why.

The numbers that Rogers Hornsby put up were just stupid. Imagine a player with a peak value of over 200. It boggles the mind. There are very few true ten win players throughout history. Imagine a guy that AVERAGED that over ten seasons. I wouldn’t make this argument now, but there is a decent argument for making him a top five overall player in the history of the sport. From there it is just semantics.

Collins was not dominant on that level, but eight win players are almost as rare. The difference is that he did it a little longer than Hornsby. He also looks more like a prototypical second baseman. The question comes in whether you want someone that flies outside the norm or whether you want someone that is about as good playing within the norm as you can find.

Nap Lajoie is something of an enigma. At his very best he was ever bit as good as Hornsby, but he had some duds in there as well. A big part of that was his value with the glove. I could buy an argument for him being second overall, but Hornsby has the top spot sewn up. So, Morgan is not a part of THAT group, but he does belong in the group of five despite the meager numbers.

These numbers demonstrate a couple of things. First, they demonstrate that Hornsby really is head and shoulders above the rest. Secondly, they reveal that Lajoie might very well be better overall than Collins. Base running is not included in OPS+, so Morgan’s advantage there is not reflected in the numbers. If ten runs equals one win then we could argue that Morgan is nine wins better than Hornsby and Lajoie as a base runner.

Numbers like rOBA and offensive winning percentage are probably better overall offensive metrics when base running is considered. This is especially true when we consider the eras these guys played in. Life was tougher in the 1960s and 1970s than it was in the 1930s. That is one reason why Gehringer’s numbers don’t look as good even though the counting numbers do.

None of these guys were top of the line fielders at the position (as we will see in other articles}. However, all but Morgan were certainly at the least significantly above average. We should talk about DWAR and FG for a second. Those numbers are based on how a player compares with the entire baseball universe.

Rogers Hornsby played more than 350 games at shortstop. Gehringer played at a time when second base defense was more valuable. It’s compelling, but only compelling in a certain context. Either way, Lajoie is the best fielder here, but it is debatable as to how valuable that is.

For those reading for the first time. The MVP points are based on a player’s finish in the award voting. MVPs are given ten points, top five finishes five points, top ten finishes three points, and top 25 finishes one point. The BWAR points are the same except they do not include top 25 points.

Like most tests, this test doesn’t prove anything on its own, but it puts each player in a slightly different light. For instance, a player with five exceptional seasons may not have the peak value that a player with ten very good seasons would have. Yet, that player may end up having more MVP points and might be remembered more fondly than a consistently good player.

Given that, we have to view Lajoie differently when looking at the BWAR points. We have to remember that the Chalmer’s Award was the first MVP award dolled out. It was not given out until 1911. Most of Lajoie’s best seasons came before then. Obviously, 19th century players would also have zero MVP points. This is one of the reasons why we also included the BWAR points.

None of these guys really distinguished themselves with their individual numbers, but we can say that Morgan and Collins have an advantage based on the fact that they played on World Series winning teams. You could make a credible argument that Morgan was the best player on the Big Red Machine. Some might point the finger at Johnny Bench or Pete Rose, but I’d argue that Morgan was even more integral to their success.

Collins was integral as a part of two different dominant teams include the Philadelphia A’s of the late 1900s and early 1910s and also the White Sox from the latter part of the 1910s. Obviously, Lajoie gets no bump at all. Hornsby and Gehringer are somewhere in between as their overall numbers were disappointing, but you could claim they didn’t have a big enough track record to really ding them that much.

When given all of the evidence, I’d say that I’d actually pick Lajoie as the second best second sacker in the game’s history, but that’s just me. Otherwise, the findings speak for themselves. The biggest upshot is that no current candidate should be compared with any of these guys.

Author’s Note: I have signed with a literary agent and launched my own site http://www.scottbarzilla.com to promote my book “The Hall of Fame Index Part II” for re-release. You can order the book there in addition to my other four books. You can also track my contributions on Battle Red Blog and my own substack page as well.